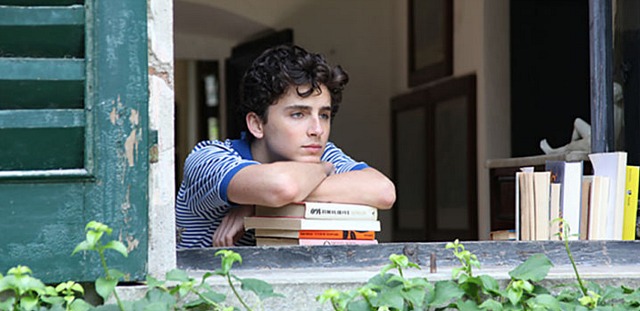

Luca Guadagnino‘s Call My By Your Name was the big winner in today’s Los Angeles Film Critics Association awards, taking the Best Picture trophy, splitting the Best Director trophy between Guadagnino and The Shape of Water‘s Guillermo del Toro, and with Timothee Chalamet taking the Best Actor prize. On top of which The Florida Project‘s Willem Dafoe won LAFCA’s Best Supporting Actor prize, and Lady Bird‘s Laurie Metcalf won the Best Supporting Actress trophy.

Call Me By Your Name has now won two Best Picture trophies (LAFCA, Gotham Awards), and is likely to win the same trophy from the 2018 Spirit Awards, which has nominated Guadagnino’s film for six awards. Chalamet has won Best Actor from both LAFCA and the New York Film Critics Circle, plus a Breakthrough Actor award from the Gothams. Dafoe seems all but unstoppable with Supporting Actor trophies from LAFCA, NYFCC and the National Board of Review. Metcalf has taken the Best Supporting Actress awards from LAFCA and the National Board Of Review.

Earlier: I was talking to a friend last night about this morning’s Los Angeles Film Critics Association voting, and he went “Yeah, well.” What, you don’t think they’re influential or at least interesting? “I don’t know that anyone cares all that much,” he replied. “They always seem to go with off-the-wall picks. We’ll see.”

Talk about flaky — the LAFCA website has a LATEST NEWS crawl on the top, and one of the headlines says “LAFCA names Moonlight as Best Film of 2016.”

10:57 am: They’re voting right now, the bagel-and-cream cheese-and-onions gang, and the first winner is…

11:13 am: Best Cinematography: Dan Laustsen, The Shape of Water. (Runner-up: Roger Deakins, Blade Runner 2049.) HE comment: What about Dunkirk‘s Hoyte von Hoytema?

11:25 am: Best Music/Score: Johnny Greenwood, Phantom Thread. (Runner-up: Alexandre Desplat, The Shape of Water.) HE comment: 1st runner-up support for Desplat plus dp Dan Lausten‘s win obviously suggests strong current for The Shape of Water. Will Guillermo’s erotic-aquatic fable take the Best Picture prize?

11:40 am: Best Supporting Actor: Willem Dafoe‘s harried, exasperated but altogether decent motel manager in Sean Baker‘s The Florida Project. Runner-up: Sam Rockwell‘s effed-up deputy sheriff in in Three Billboards outside Ebbing Missouri. HE comment: Okay, fine.

11:51 am: Best Production Design: Blade Runner 2049‘s Dennis Gassner. Runner-up: The Shape Of Water‘s Paul D. Austerberry. Excerpt from my BR49 review: “Deakins has done his usual first-rate job here and everyone knows he’s well past due, but the real whoa-level work is by production designer Dennis Gassner and supervising art director Paul Inglis.” HE comment: Another Shape of Water runner-up vote! Clearly there’s a hardcore contingent that will vote for Shape of Water in any category, come hell or high water.

12:01 pm: Best Editing award goes to Dunkirk‘s Lee Smith. Runner-up: I, Tonya‘s Tatiana S. Riegel.

12:06 pm: Lady Bird‘s Laurie Metcalf win LAFCA’s Best Supporting Actress award. Runner-up: Mudbound‘s Mary J. Blige.

12:17 pm: Winner of LAFCA’s Documentary/Nonfiction award is Agnes Varda and JR’s Faces Places. Runner-up: Brent Morgen‘s Jane, a doc about chimpanzeetarian Jane Goodall, which had its big L.A. premiere at the Hollywood Bowl.

[Brunch break] [HE nap break]

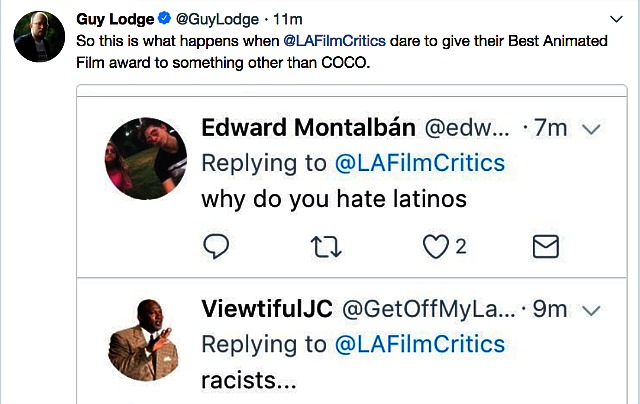

2:09 pm: For LAFCA’s Foreign Language Film award, a tie between Robin Campillo‘s BPM (Beats per Minute) and Andrej Zvyagintsev‘s utterly brilliant Loveless. LAFCA’s animated feature award went to The Breadwinner and not Disney’s Coco. The Best Screenplay award was won by Jordan Peele‘s Get Out. Runner-up: Martin McDonagh‘s screenplay for Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri.

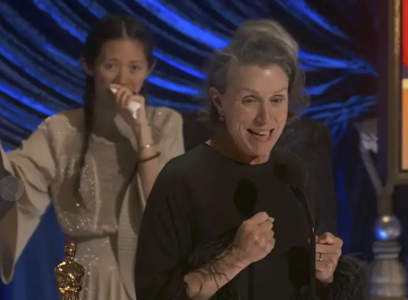

3:15 pm: LAFCA’s Best Picture of 2017 is Luca Guadagnino‘s Call me By Your Name — all is forgiven, no more bagel and cream cheese jokes until next year. Runner-up: The Florida Project. The Best Director Award is a tie between CMBYN‘s Luca Guadagnino and The Shape of Water‘s Guillermo del Toro. Best Actor is CMBYN‘s Timothee Chalamet (runner-up: James Franco, The Disaster Artist). The Best Actress award has gone to The Shape of Water‘s Sally Hawkins

Earlier: If I was there voting with Bob Strauss, Myron Meisel, John Powers and the rest of them, I would toast my bagel just so, going for a nice light brown color. Then I’d add a schmear of Philadelphia 1/3 Less Fat Cream Cheese, a few slim rings of red onion, a thin slice of lox, some diced Roman tomatoes.